The sea from above: the gaze of the marine ecologist

Reading time

0 min

An NBFC project uses drones and multispectral cameras to investigate biodiversity

When it comes to assessing the health of everything that lives in the sea, marine ecologists come into play. Gennaro Ucciero is one of them, and his doctoral project (carried out between the University of Palermo, the NBFC office in the Sicilian capital, the Laboratory of Marine Ecology at the Federico II University of Naples and the PRISMA Lab at the same university) puts a twist on traditional survey methods.

Protagonists of the interview

Gennaro

Ucciero

- Marine Ecologist

- University of Palermo – NBFC – University Federico II

- gennaro.ucciero@unipa.it Copia indirizzo email

Andrea

Capuozzo

- Engineer

- PRISMA Lab – Federico II University

- andrea.capuozzo@unina.it Copia indirizzo email

Technology and marine ecology: a changing story

“In the old days,” Ucciero explains, “a major part of research activities took place in the laboratory. The ecologist or marine biologist would first choose a reference area, even better if it was accompanied by historical data. Then they would go to the field, that is, to the sea, dive and collect samples. These samples (of seawater or any living species) would then be analyzed in the laboratory.”

The big change of pace came with the invention and spread of the Internet , which, even in this discipline, “opened wide the door to a range of knowledge that was previously very difficult to come by. From there on, technology developed at previously unthinkable rates. More and more oceanographic stations appeared, and oceanographic ships with advanced technological means, including robots for underwater surveys; countless technological instruments were developed. And today we are here.”

A project with a fresh look

The instrumentation Ucciero deals with, drones, have been established presences for decades in various fields; but the application of them to the study of biodiversity is a major innovation. “In our laboratory we are involved in monitoring marine environments, and with me we started to study and use drones with the same goal. On these devices, which are true unmanned mini-helicopters that can be remotely controlled or fully autonomous, we mount a multispectral camera that can photograph different bands of the visible spectrum. Specifically, we use a five-sensor camera. One is color (which is the classic camera), and the others are green, red, infrared, and near-infrared. Thanks to this instrumentation, which captures the light reflected by various organisms with its shots, we can “see” a certain area while standing at a distance, without the need to dive or physically collect samples as was the case before.”

Collaborating with Gennaro Ucciero is Andrea Capuozzo who, as an engineer (his doctorate is under the PRISMA Lab), focuses on the more technical part of the project.

His presence is also crucial because two people go into the field in these cases: one researcher acts as a pilot, the other as support, including for the calibration phases.

Requirements for top-down research

The study area being considered is Porto Cesareo, in Puglia. “There are many characteristics that make for a perfect field day,” Capuozzo specifies. “First and foremost, the weather conditions: the sea must be flat and it must not be too hot, otherwise the drone’s batteries go into overheating, forcing the pilot to bring the drone back in and making it impossible to use or recharge them until they cool down. Then, if the reconnaissance is done between 7 a.m. and 10 a.m., excessive sun glare, typical of the middle hours of the day, is avoided. Finally, some clouds are welcome because they partially shield the sun.”

A very careful look

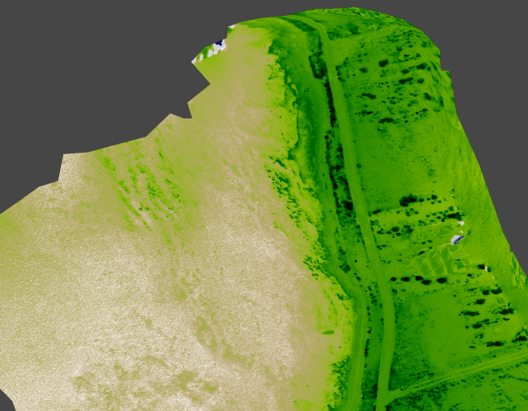

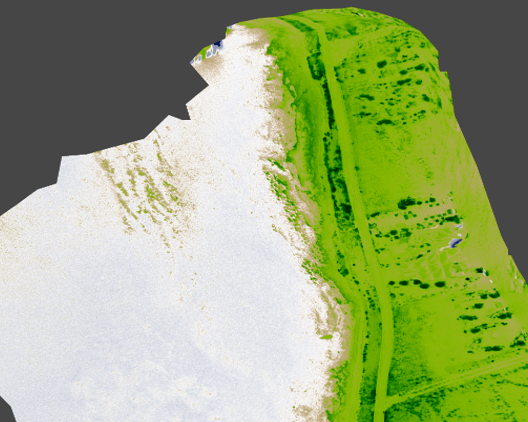

The pilot and mount are required for safety issues, but on the drone (a DJI Array 300) the area of interest is set from the beginning, to make it move on autopilot. Once airborne, having reached the appropriate height (between 50 and 100 meters), the device covers the designated area (in the Porto Cesareo project, 64 thousand square meters) moving in a zigzag pattern like a printer’s needle. Each image taken by the device, georeferenced, is then interpolated by software that composes, piece by piece, an accurate map.

The campaigns involving Ucciero and Capuozzo’s projects are conducted at multiple times of the year. At Porto Cesareo, the two researchers’ drone, passing and repassing over the same study area, captured, for example, the seasonal variation in algal communities. More or less bright coloration, or extensions of color that change size, are indices of biodiversity that are then interpreted by scientists.

“After making these maps,” Gennaro Ucciero resumes, “we verified them with divers. We asked them to do the so-called ‘sea truth,’ that is, to go to specific points indicated by us to confirm or deny what our survey showed. So far, the use of the drone has proven to be completely reliable.”

Future projects in the pipeline

The next horizon for this new approach to studying biodiversity is the development of an amphibious model. “The doctoral project,” Ucciero explains, “will see the use of a new amphibious drone for sea surveys developed in collaboration with the PRISMA Lab and Neabotics, a start-up born from the latter.”

“The goal,” Andrea Capuozzo concludes, “is to develop, together with Neabotics and TopView (an SME specializing in integrating drones into business processes and low altitude airspace, ed.) a new amphibious drone. In addition to photo-sensing missions, the drone will be able to perform in situ measurements and surveys using a probe that will descend into the depths, providing marine biologists with essential data for their analysis. The final product will combine flight capabilities with a catamaran-like design, equipped with marine thrusters that will allow it to sail as well as float.”