Small, autonomous and affordable: OpenSwap

Reading time

0 min

A possible ideal solution for exploring the biodiversity of less accessible coastal areas

Studying the biodiversity of Italy’s coasts required, until yesterday, suitable boats, large teams, sophisticated machinery and substantial funds. The development of a small, low-cost autonomous vehicle changes the scenario and opens the door, potentially, to more frequent campaigns and more accurate data, within the reach (even) of small administrations.

Protagonists of the interview

Giuseppe

Stanghellini

- Research Technologist

- CNR – Ismar

- giuseppe.stanghellini@cnr.it Copia indirizzo email

“For ships, which ‘fish’ a lot, coastal habitat is often difficult to investigate,” explains Giuseppe Stanghellini, research technologist at CNR-Ismar in Bologna. “Obvious navigability problems prevent them from getting too close to land. Now, however, thanks to a new device, we can overcome this limitation.”

“Studying coastal habitats with an autonomous vehicle that is reliable, easy to deploy and inexpensive has tremendous advantages.”

Giuseppe Stanghellini,

CNR research technologist – Ismar

With the gaze (and tools) of geophysics

Stanghellini is a physicist – indeed: a geophysicist. ” Geophysics,” he explains, “is the discipline that studies the physical properties of the Earth to understand its structure. And it is also useful for investigating biodiversity.” In his work, he uses and develops survey instruments that use the principles of physics to discover the characteristics of the aquatic environment.

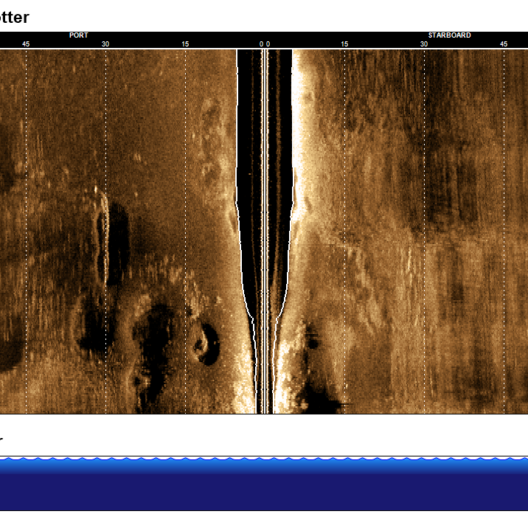

The protagonists of his current research are two. The first, the side scan sonar, is a device that, placed on a boat, sends acoustic waves to the seabed and then detects its reflectivity.

What results are detailed representations of the seafloor that, however, he clarifies, “are not optical images, that is, in the visible. It is as if we are looking at the seafloor with our ears,” he adds with a smile.

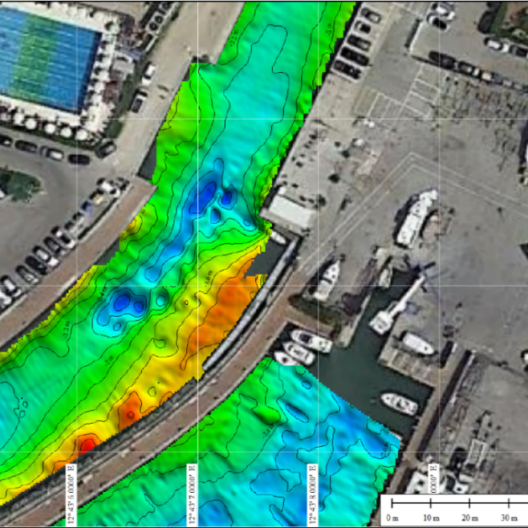

The second instrument employed by Stanghellini is the multibeam echo sounder, which “always uses the principle of sending acoustic waves to the seafloor, but in this case it records their travel time.”

Through the use of dedicated programs that analyze the return times of sent acoustic signals, Stanghellini is then able “to understand and define bathymetry, that is, the morphology of the seafloor.” In this case, what results is a three-dimensional reconstruction of the seafloor, even at ocean depths.

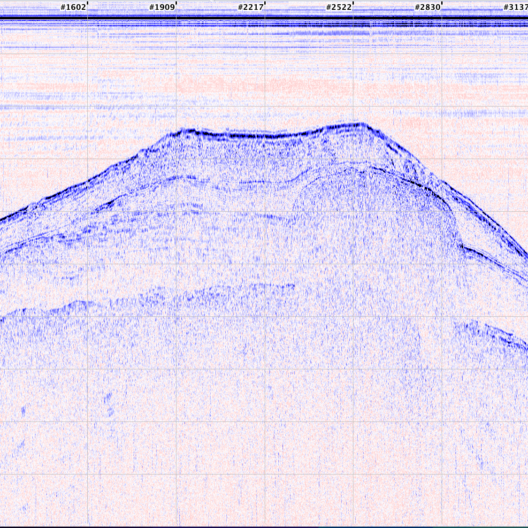

“Then there would be a third tool,” the researcher continues, “which allows us to do a stratigraphy of the seafloor, that is, to see what is under the seafloor.

It is the sub bottom profiler, and even the latter, albeit indirectly, can prove useful in investigating biodiversity.”

The advantages of small size

All this equipment, sophisticated and extremely specific in its use, is present in Gaia Blu, the CNR’s oceanographic ship. But the problem arises when surveys of this kind-even for vessels of much smaller tonnage-must be conducted close to the coast. And here comes the solution.

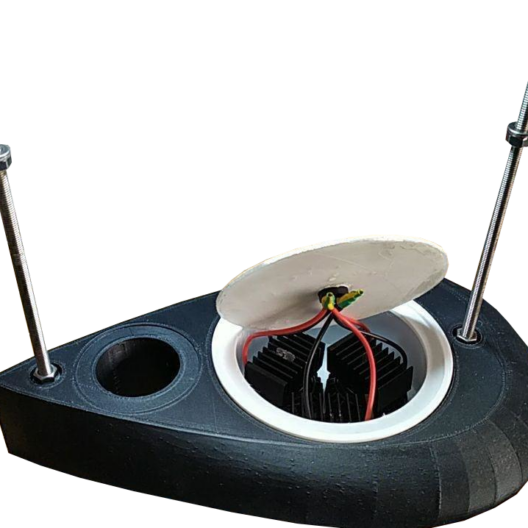

With NBFC, for about a year now, Stanghellini has been working on theinstallation of these tools on an autonomous vehicle, called OpenSwap (“open” because at its core it also makes use of hardware/software platforms that are “opensource” in nature; SWAP stands for Shallow Water Prospector), developed thanks to a POR-FESR grant from the joint CNR – Ismar / Proambiente Consortium research group.

The expression “autonomous vehicle” denotes a small and lightweight mobile platform with extraordinary features – starting with its size. Its 120×120 cm can be easily loaded onto a car; light and agile, it can get within a stone’s throw of the coast. It can store specific routes with extreme precision and retrace them years later, “making a four-dimensional study possible: in other words, it shows changes in different parameters, or habitats, over time.”

The OpenSwap with integrated multibeam enables mapping of habitat extent at very high resolution. In the coming months it will be tested off the coast of Campania to monitor the valuable and vulnerable habitats found on the Santa Croce Bank in the Punta Campanella Marine Protected Area.

The Adventures of OpenSwap

When sent on a mission, OpenSwap-which has enough battery power to travel 25 kilometers-is instructed on the route to be followed, and adheres to it with great rigor. “Devices like this,” the researcher continues, “can reach places that are inaccessible, or protected, or dangerous: we used it in Antarctica to do surveys at the base of glaciers, where boats could not venture because there were always risks of collapse. And they can work both day and night, sailing undaunted at four kilometers per hour, which is roughly equivalent to two nautical knots.”

Few limitations and many advantages

Of course, with small size also comes limits: “the vehicle is tiny, so we cannot mount 100 kg of instrumentation on it. And you have to deal with battery life, which we never take to the limit. But I think this solution is a winner, also because of the cost.”

To implement OpenSwap, which must be ordered from the manufacturer, requires 15 thousand to 18 thousand euros for the basic version, a price that cuts down on the cost of campaigns carried out by traditional means.

“Studying coastal habitats with an autonomous vehicle that is reliable, easy to deploy and inexpensive has tremendous advantages,” Stanghellini concludes. “Its cost can also be addressed by local governments, and cutting costs means being able to increase the frequency of campaigns. Surveys, even over time-for example, after a storm surge-can be more accurate; much less staff is needed than with traditional techniques (two or three people are sufficient). The study of coastal biodiversity can benefit greatly from its adoption.”

I have always liked water and the sea. For a physicist like me, doing research in marine science offers a wide range of possibilities: all the instrumentation used in this field is based on the knowledge I have acquired in my subject of study.

Giuseppe Stanghellini, Research Technologist, CNR – Ismar