Reading time

0 min

In their invisible world, biodiversity comes to life

Paola Branduardi is full professor of Chemistry and Biotechnology of Fermentations at the University of Milan Bicocca. Her voice and enthusiasm accompany research that, thanks to her work with NBFC, tries to radically change our relationship with microorganisms, the true protagonists of the ecological and industrial transition. With clear words and vivid images, he guides us into the fascinating world of invisible life.

""

Professor Branduardi, what is your role within NBFC?

“We want to enhance microbial biodiversity. If we think that “biodiversity is the solution,” then microorganisms are its primary promoters and actors. We have known some of them for a long time: they are the ones that can make wine, beer, cheese. But today we are not stopping at the food chain-which, too, with the world’s population growing steadily, will be an increasingly pressing issue. Microorganisms can give us so much more.”

""

Huge and tiny wealth

Help us visualize: we are used to thinking about the richness of biodiversity at other scales, and it is intuitive to understand that a forest with many animal and plant species is richer than a forest with 100 thousand fir trees. How can we visually imagine biodiversity in the tiny world of microorganisms?

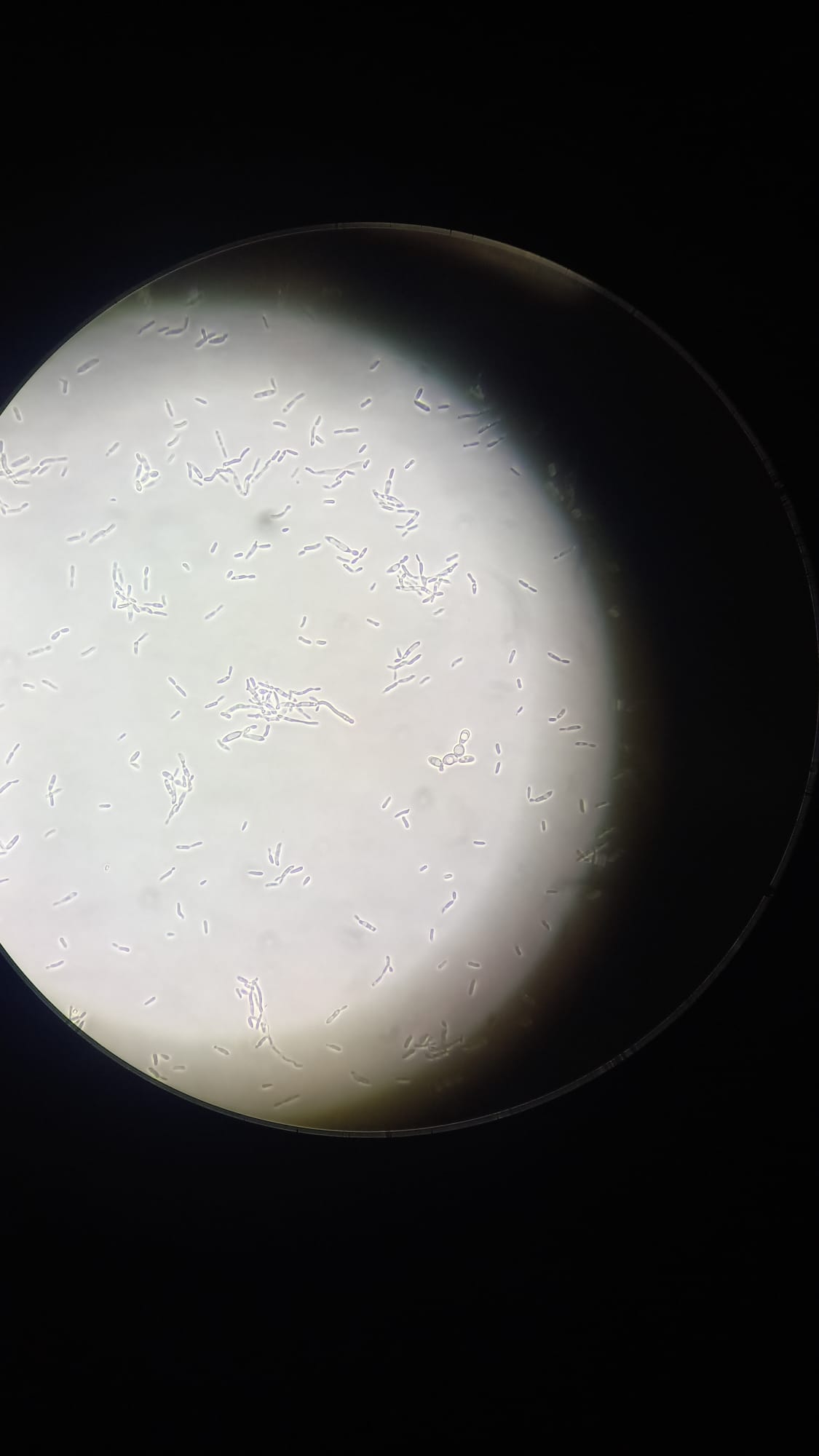

“First, we can remember that microorganisms were the last to be discovered, for the simple reason that to see them you first needed to invent the microscope. Yet they were the first inhabitants of the Earth, four billion years ago. They are the ones who organized their own molecules into independent life forms. Not only that, microorganisms continue to amaze us because they are able to colonize environments we thought incompatible with life; instead, the simplicity and efficiency with which they organize their cellular form allows them to have incredible behaviors. An image that microbiologists like so much is this: there are more microorganisms on Earth than there are stars in the universe. Their number of species, worldwide, should be around a billion. So the biodiversity of the planet is, first of all, microorganisms.”

""

So microorganisms are the very basis of biodiversity functioning?

“Exactly. Some say we know only 1% of this diversity, some say 10%. Even if it were 20%, that would still leave 80% to explore. Microorganisms invented the biogeochemical cycles that regulate life. If they decline or are bad, life itself is bad. We need water, oxygen, nitrogen; plants, to fixCO2, need light. Microorganisms need much less. They are life forms that can rely on five metabolic pathways, four of which do not depend on light. One example: they can fix carbon dioxide even in dark environments, so they can do so even in industrial reactors, and turn it into larger molecules. In other words, we can use spent gases enriched with carbon monoxide andCO2 to build a kind of small modular bricks that are used to create new products.”

""

Research and industry, a marriage that works

In terms of disclosure, what does your research consist of?

“We are inspired by nature, but we know that industrial processes move away from it. It is not enough to know the microorganisms: we have to accompany them in industrial processes where they will have to give their all to produce products with competitive performance compared to those of current petrochemical supply chains.”

""

Does this mean that the relationship with industry is an integral part of your research?

“That’s right. Sometimes we start from a basic study and already have an application in mind. Other times we have a problem to solve. One more example: solvents, which are very polluting. We work on enzymes that produce “green” solvents, with very little impact, through biotransformation. Companies are very interested in products like these. The processes and applications we are studying are many, but they all have the same purpose: to imagine what society needs and to try to understand how microorganisms can help us. There is one characteristic of them that is extraordinary: they are able to use lots of substrates, eat them and produce substances that eventually someone else can eat. Taken as a whole, they are able to move matter around and continue, by cycles, to put it back into motion within a biosphere-in the case of Earth, ours.”

""

Safe and sustainable, right from design

How does your research translate into practice?

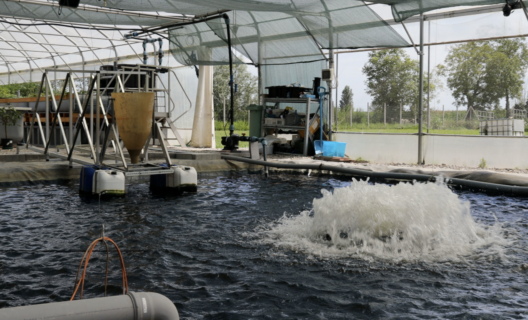

“We have already identified interesting potentials of many microorganisms. These potentials of theirs we try to unlock them, maximize them and then test them in environments that mimic the industrial condition. There is a term, “biomanufacturing,” that means just that: making microorganisms and their enzymes do things with as little impact as possible. With a team of almost a hundred researchers across Italy, we work on various fronts: green solvents, fabric dyes, nutraceutical molecules, enzymes to degrade plastics. Then there is a group that is working on designing materials with sustainability in mind from the very beginning. This logic, “safe and sustainable by design” is wonderful. Once, at a conference, the speaker told us, “Close your eyes and try to imagine how many of the things you came here with today you will still have with you in two years. And then think about the impact we have on our surroundings.” This is a constant thought for us. What we are trying to do is to change mindsets.”

""

The potential of microorganisms is largely unexplored. But then, with such vast biodiversity, how do you know who is doing what?

“Good question! Some microorganisms we know well, and we can work together with their natural capabilities (some, for example, produce carotenoids, important antioxidants) or we can engineer them: that is, we add gene elements, from other organisms, to make them do new things. We are at a time when of biology-which will always retain a complexity that we aspire to understand-we have understood numerous mechanisms, and so of the “assembly box of life” we know quite a few “pieces.” So let’s get even more creative: let’s try to abstract concepts and move them from a natural to an industrial context.”

""

Food and waste, two frontiers of interest

What are some other areas of your interest today?

” Food: we need new characteristics in foods, different from those in some mass-produced foods. Microorganisms can help us by producing nutraceuticals, or compounds that are beneficial to health, without consuming soil. And then waste: microorganisms can eat it and turn it into new value. These are two of many examples by which our research can impact society. Those who do this work know that sustainability always has three legs: the environmental aspect, the economic aspect and the social aspect. For something to be sustainable, these three aspects must coexist. And as a scientist working in industry, I know that we have to propose sustainable solutions to industry, otherwise they will never become reality.”

""

That of waste is a truly impactful horizon.

“Yes, very much so. We have been fortunate to interface with production chains many times: for companies, the issue is a hot one, because waste has a management cost. To cite an example: sugar, in Europe, is made from sugar beet. What remains after its processing is beet pulp and molasses, which cannot always be reused. We combine these two elements with waste glycerol, feed them to microorganisms, and get antioxidants for functional foods. Another example: the group at the University of Naples Federico II is working on unique microorganisms that live in extreme environments such as sulfataras or calderas, which possess enzymes that can degrade traditional plastics, such as PET, and in return produce compounds that, thanks to fermentations carried out by other organisms such as those developed in our laboratories, can be used in cosmetics. There are many companies-I am thinking for example of Novamont, which also works with NBFC-that have as their mission the creation of materials endowed with the virtuosity of resource circularity, and sustainability. It is up to us scientists, in this scenario, to give not only the quality, but also the quantity. We need to be able to describe our processes quantitatively, so we can make prospective assessments.”

""

Between research and industrial application

So is yours always an efficiency argument?

“Certainly. With NBFC we work between research and industrial application. We conduct our experiments under conditions that are as close to industry as possible-then it will be up to industry itself to decide whether or not to invest, and how. One thing, however, is clear to us: investing in these projects today means investing in innovation; and investing in innovation means remaining competitive, and being the first, tomorrow, to have already made this revolution. This is a choice that Europe needs.”

"Are SMEs also able to participate in these kinds of innovations? “Yes, of course. Think of new, or extremely specific, solutions: some people produce a particular enzyme that is used to detect food fraud, others a food or textile dye. One production, even on a small scale, is enough to produce a diagnostic kit. And everything, in this case, can work economically even on a small, albeit industrial, scale.”"

Paola Branduardi

Are SMEs also able to participate in these kinds of innovations?

“Yes, of course. Think of new, or extremely specific, solutions: some people produce a particular enzyme that is used to detect food fraud, others a food or textile dye. One production, even on a small scale, is enough to produce a diagnostic kit. And everything, in this case, can work economically even on a small, albeit industrial, scale.”

""

In search of new antibiotics

One last area of application you would like to mention?

” Biodiversity mapping. For example, in a project we carry out with the company Aboca, in a joint effort of multiple NBFC spokes. We collect samples in areas where there is extensive drug use, to see how biodiversity may be affected, or conversely how it may prove to be our ally in biodegradation. Again, we collect samples in areas that are heavily anthropogenically impacted, and try to characterize how the microbial response is affected by various factors. This links us to another major area, as microbial responses include the production of bioactive molecules, among which we research potential new antibiotics, which are increasingly needed because of the spread of multidrug-resistant bacteria.”

""

His enthusiasm is infectious. Where does he come from?

(laughs) “My fascination with microorganisms was a late discovery. I started out as a zoologist (I wanted to study cetaceans), but then I worked for five years on the central nervous system. As a cell biologist, I realized I was missing the molecular part a little bit, so I did a PhD in molecular biology, and then a postdoc in biotechnology. So I found that working with companies was really interesting. I learned to expand the logic with which to develop projects and to write patents, which is a fantastic intellectual challenge. So … of course I’m excited! I discovered a lot of new things for myself that I hope will be useful for others as well.”

Protagonists of the interview

Paola

Branduardi

- Professoressa ordinaria di Chimica e Biotecnologia delle Fermentazioni all’Università di Milano Bicocca

- Università di Milano Bicocca/Spoke 6

- paola.branduardi@unimib.it Copia indirizzo email

Listen to other voices

Discover other voices and new perspectives: biodiversity told by those who study it, protect it and make it known