Cyanobacteria and nutraceuticals, together today

Reading time

0 min

Ancient bacteria are a valuable and sustainable resource for the production of bioactive molecules

In the second year of her doctorate in drug science, Teresa De Rosa, at the Federico II University of Naples, studies cyanobacteria, single-celled organisms without which the world as we know it would not exist. Some of the oldest bacteria on Earth, with fossil records dating back at least 2.1 billion years, these microscopic organisms are the focus of her research for several reasons: De Rosa studies their biodiversity, prevalence and potential.

Protagonists of the interview

Teresa

De Rosa

- PhD student in drug science

- Federico II University of Naples

- teresa.derosa@unina.it Copia indirizzo email

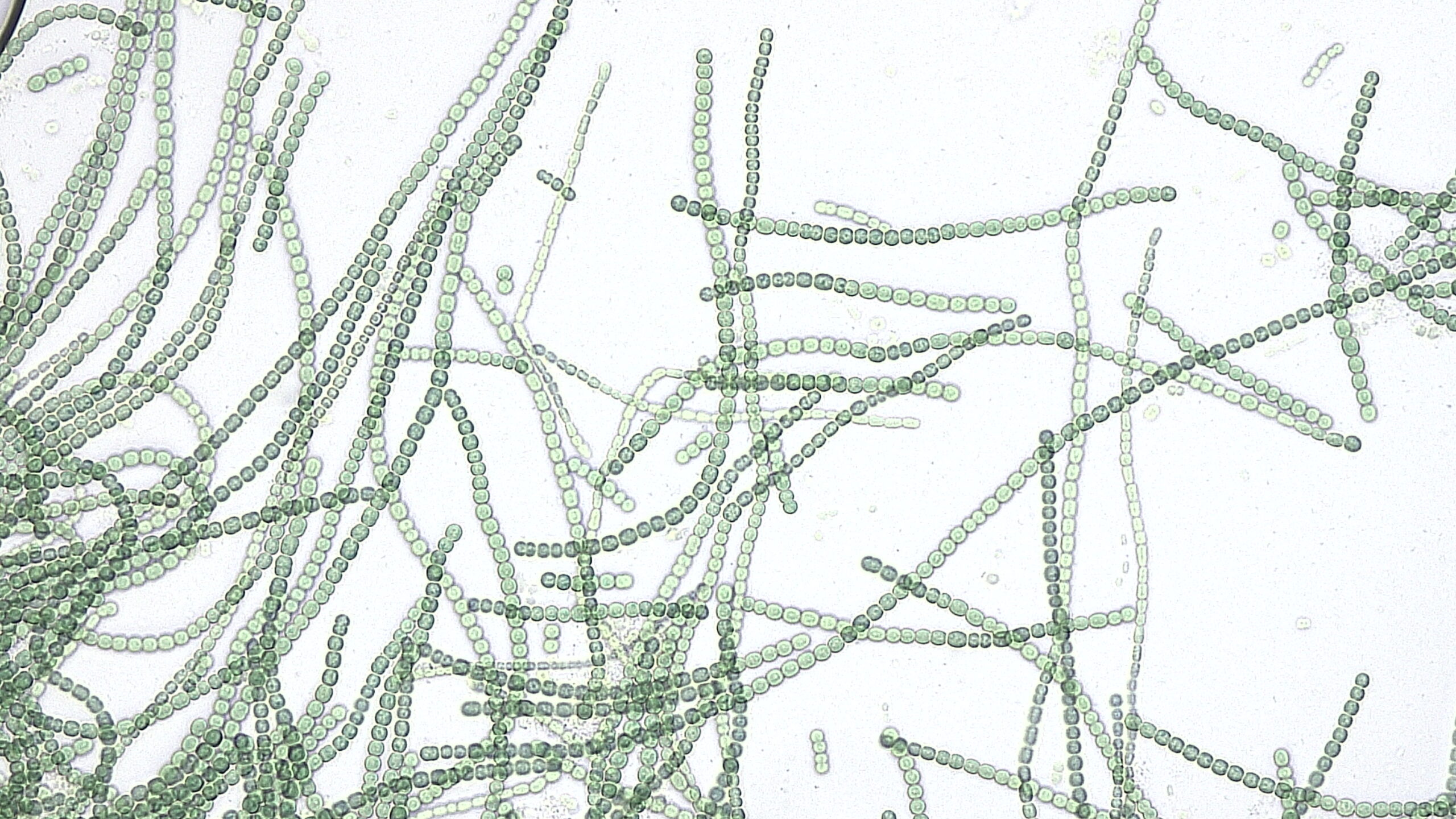

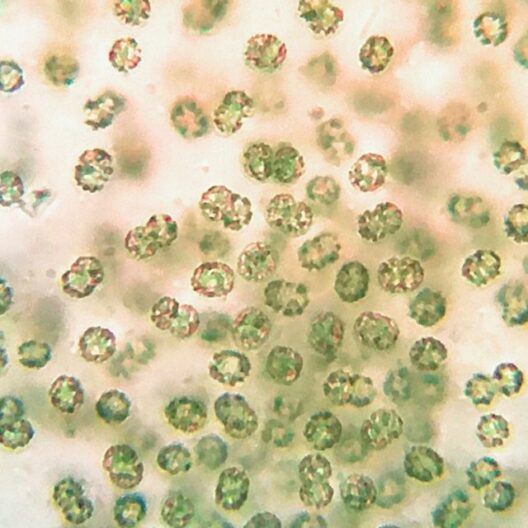

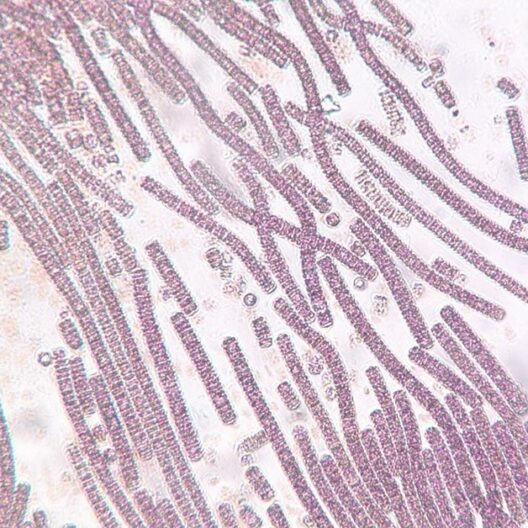

“Cyanobacteria are ubiquitous organisms,” De Rosa explains, “that we find in both fresh and salt water: seas, lakes, rivers and ponds can provide ideal habitats for them. These organisms, which have a characteristic blue-green color, are bioindicators of the health of the environment. In places where they find high temperatures, alkalinity, waste discharges or human-caused pollution — that is, an excess of nutrients, especially phosphorus and nitrogen — cyanobacteria proliferate to form blooms( bloom in English) characterized by the appearance of thick layers on the water surface.”

Dual-natured organisms

Dedicating ourselves to cyanobacteria means first of all discovering their best and most critical sides. On the one hand, De Rosa explains, they are a valuable and sustainable resource for the production of biologically active molecules: “In our group, TheBlueChemistryLab, coordinated by Prof. Valeria Costantino of the Department of Pharmacy at the University of Naples, we study a species of cyanobacteria called Anabaena flos-aquae.

This species has a special feature: it produces siderophores, or compounds that chelate (i.e., transport iron with it, ed.). This aspect, we believe, could be of great interest to nutraceutics (the field that studies nutrients in foods that have health benefits, ed.).”

The other side of the coin is that cyanobacteria, during their bloom, can also be harmful to human health, animals and the environment. In addition to producing toxins (the so-called cyanotoxins cause, in some cases, skin irritation, gastrointestinal problems, and, in severe cases, liver damage), their blooms can in fact cause ecological damage such as a decrease in oxygen in water bodies, which can lead to damage to aquatic life, or create disruptions to recreational activities such as swimming or boating, or even to fishing, the local economy and tourism. “We know that cyanobacteria have a kind of dual nature, and that makes the research even more interesting.”

The confrontation with citizenship

“An important part of our work,” De Rosa continues, “is monitoring, to keep an eye on the situation. Our area of reference is Campania, where we monitor two types of places: those in which blooms historically occur, to see their evolution, and those where new blooms are reported to us. We have also devoted some effort to communication, to involve citizens in these reports. We have explained to the public that when they come across some blooms of cyanobacteria-which can be recognized because they look like thick mats, patches or stripes on the surface of the water, sometimes foamy, green or greenish-blue or even reddish-brown-they can contact us. We come, take samples and get important information from them.”

Between analyses and discoveries, the research continues

The monitoring carried out by De Rosa and colleagues consists of taking samples (of water and biomass) and analyzing them in the laboratory-an activity that moreover “also allows us to explore the biodiversity of these aquatic organisms: hundreds of species are already known to science, but much remains to be discovered about them. Our research group, for example, has identified a new genus of cyanobacteria in the San Filippo thermal baths in the province of Siena.” Microscope analyses are followed by chemical ones, where the protagonist is a mass spectrometer coupled with liquid chromatography “of the latest generation. Today we can count on unprecedented sensitivity and accuracy,” the scientist specifies.

Sampling, analysis with sophisticated instrumentation and tantalizing hypotheses are constantly intertwined in the work of TheBlueChemistryLab. Interesting news is expected from this group of scientists soon.